by

Esther Mar

| Jun 22, 2018

There is a book I am hoping to locate and read called “Ribbon of Fire” by Jonathan Aylen and Ruggero Ranieri. Abstracts say that it reviews economic and technological developments showing how the wide hot strip mill evolved in the USA from narrow (3” max) hot strip mills rolling ‘hoop’ in the 19th century, through 4” mills rolling ‘skelp’ to 7” wide mills rolling 100’ lengths by 1890. Widths and lengths rolled slowly progressed - 24” wide and 500 – 1000’ long - and then a breakthrough was made in 1923 by an engineer at Armco and in January 1924 the first 36” wide hot strip was rolled in the multi stand mill in the Middletown Works, in Ohio. This was rapidly followed by an improved 36” mill at the Columbia Steel Co. at Butler Pennsylvania, which soon was widened to 48”. The main innovation of this mill was a four high finishing stand using a small diameter work roll supported by a larger back up roll, this enabling greater reduction between passes. It is from this mill design that all future wide hot strip mills developed.

From the technology of the four high mill stand stems the understanding of gauge performance of sheet products. I say “sheet products” because as the product range of these mills increased, governing bodies differentiated between “sheet” and “strip”, the latter being rolled in narrow mills. For example, ASTM A568 (Steel, Sheet, Carbon, Structural and High-Strength, Low-Alloy, Hot-Rolled and Cold-Rolled, General Requirement for) classifies “hot rolled strip” as material with mill edges 12” and less in width. “Hot rolled sheet” is further reduced in wide cold reduction mills to produce “cold rolled sheet”. But “cold rolled strip” is rolled in “strip mills” that are narrow cold mills. The raw material for it is generally “hot rolled sheet” that has been pickled and slit into narrow widths. The end product has thickness variation which is less than sheet mill industry tolerances and is often produced to custom characteristics.

The following text deals with thickness variation in hot rolled and cold rolled sheet but uses the term “strip” because it is the commonly used terminology in the trade.

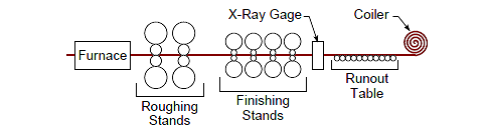

The process of creating a finished flat rolled product from a slab consists of several stages. These stages in a typical hot rolling mill are: reheating the slab, roughing, finishing, measuring, cooling, and coiling. As the hot steel travels through the process its thickness is successively reduced in the various mill stands.

The finishing process gives the strip its final dimensions. The strip thickness (and flatness) is measured in real time by X-Ray gauges at the exit of the finishing stands. Measuring the final dimensions of the strip is critical for the mill controllers as they adjust the mill parameters in real time with feedback from the gauges to minimize variation in thickness (and shape).

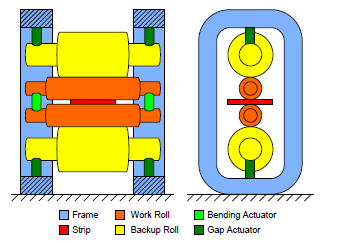

The concept of the mill stand mentioned at the end of the first paragraph is shown below. A stand like this is several stories high. It is composed of a set of work rolls between which the strip passes, a set of backup rolls, which are bigger, and actuators to control the gap and the bending of the rolls, all supported by a frame.

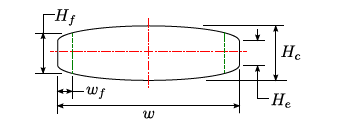

Rolls consist of two parts: barrel and neck. The barrel is the part of the roll that comes into contact with the strip or another roll. The neck is the thinner portion of the roll, part of which rests in a bearing. The bearing is held by a chock which is connected to the stand frame. As the hot strip travels through the stands there is force on the rolls which causes their deflection and resulting strip deformation. This force, as well as other factors (including roll thermal profile, roll wear, strip width) affects the cross width dimensions of the strip. The resulting cross section of the strip looks as in the schematic below.

Most mills refer to the overall cross width configuration as the “profile” which is composed of the edge drop off, or feather, and the crown. The crown is the difference in thickness between the thickness at the centre of the strip and the thickness at the end of the edge drop off, or feather (usually about 2” in from the mill edge).

The profile of the strip is generally consistent from the lead end of the coil to the trail end of the coil although it can vary towards the coil ends. Separately, there are methods in modern hot strip mills that are used to control the shape of the strip (both in terms of flatness and crown). These include: roll bending, roll shifting, and inflating roll (variable crown roll).

When hot rolled strip is cold reduced the aspect ratio of the hot strip profile is maintained but the magnitude is proportionally smaller in the cold rolled product.

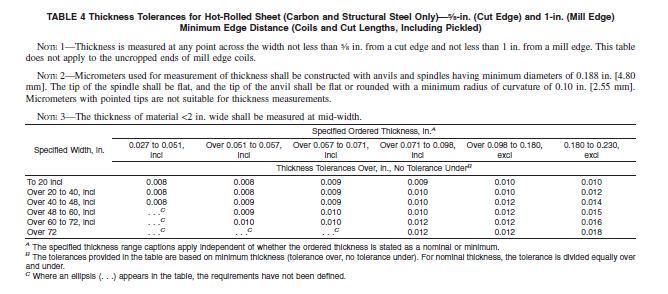

The following table from ASTM A568/A568M – 13a provides the tolerances for hot rolled sheet steel. The tolerances include variation along the coil length and across the coil width. The variation attributable to the profile can be in the order of 1 – 5% of the average thickness depending on a variety of factors.